Say Hello to Hart Club

Helen Rali Article, Issue Two

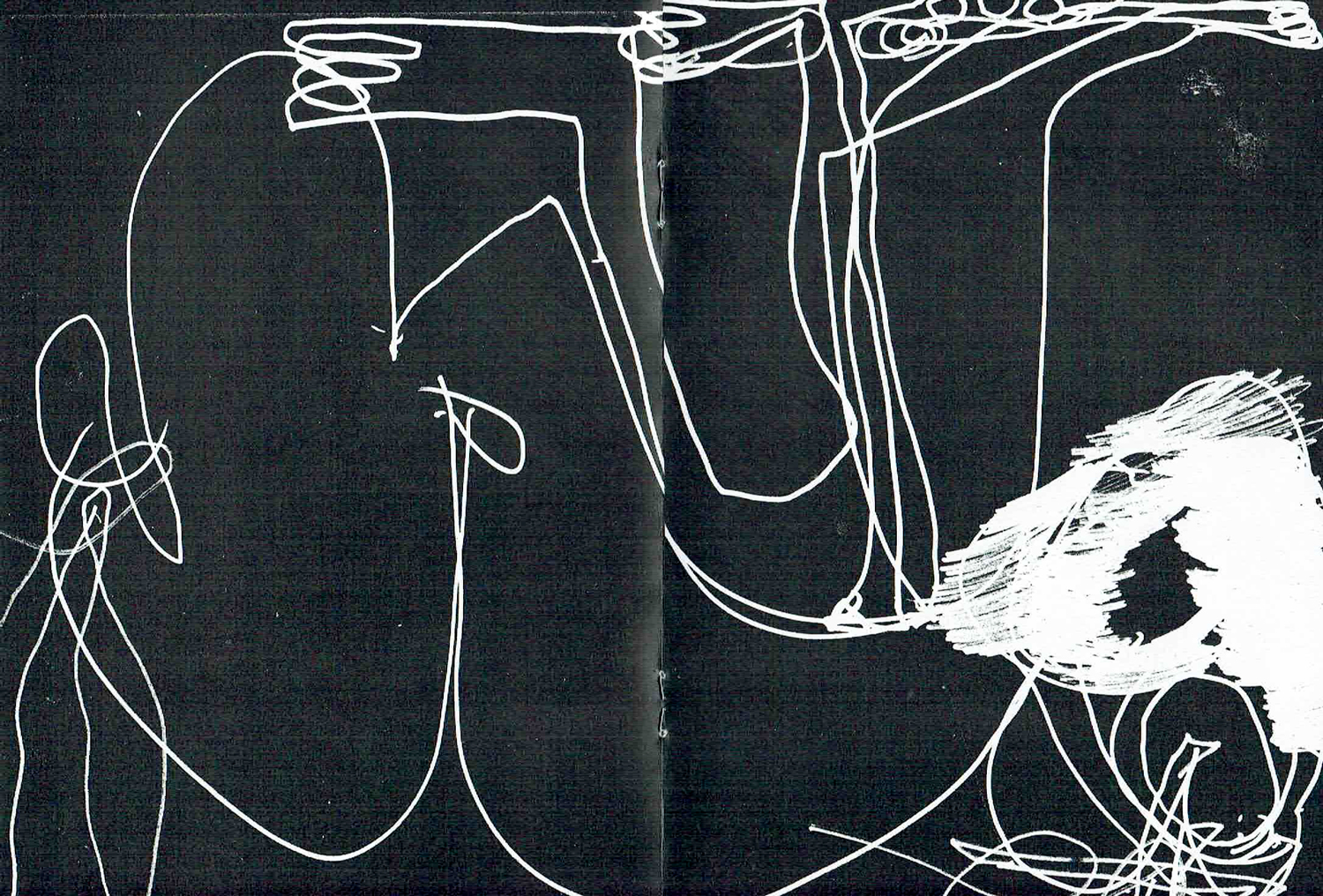

Article, Issue TwoDrawings by Andy Ogungbemile & Donal Stuart

Helen Ralli is the founder of Hart Club: a gallery that opened in 2018 dedicated to championing Neurodiversity in the Arts, which creates space for community-focused activity in an increasingly impossible city.

In 2017, while I was curating an exhibition which celebrated neurodiversity called Great Minds Think Different, I had the great fortune of meeting The Camberwell Incredibles. This collective is formed from a group of 12 learning-diverse adults based in a social action centre in South London, who meet twice weekly to socialise and create art.

I was blown away by the innate honesty and vibrant expression that underpinned their various practices; so much so, that they ultimately inspired the creation of Hart Club. It was the first time in a long time I’d felt excited in a visceral sense about art. There’s nothing like the commercialisation of everything to suck the joy out of something, so to find a group of artists seemingly unweighted by the notion of external judgement and financial capital is a sacred thing.

In 2017, while I was curating an exhibition which celebrated neurodiversity called Great Minds Think Different, I had the great fortune of meeting The Camberwell Incredibles. This collective is formed from a group of 12 learning-diverse adults based in a social action centre in South London, who meet twice weekly to socialise and create art.

I was blown away by the innate honesty and vibrant expression that underpinned their various practices; so much so, that they ultimately inspired the creation of Hart Club. It was the first time in a long time I’d felt excited in a visceral sense about art. There’s nothing like the commercialisation of everything to suck the joy out of something, so to find a group of artists seemingly unweighted by the notion of external judgement and financial capital is a sacred thing.

It was the first time in a long time I’d

felt excited in a visceral sense about art.

There’s nothing like the commercialisation

of everything to suck the joy out of

something, so to find a group of artists

seemingly unweighed by the notion of

external judgement and financial capital

is a sacred thing.

In the face of this brilliance, what didn’t add up was that in the twenty or so years of their existence as a collective, they had never had a public-facing exhibition in a gallery. It’s no secret that people who have additional needs or have different ways of communicating and behaving are often excluded from mainstream society. As a result, their creative output lies in the shadows.

The broader social implications of this kind of invisibility, or lack of contact, often result in categorisation and negative stereotyping. Our inaugural collaborative exhibition title Training, is a great example of the ways we are trying to challenge these issues. Donal Sturt is a painter and graphic designer I have always really admired – his work is thoughtful, super polished and concise. He came to the Great Mind’s Think Different exhibition, and was so taken by the work of an autistic artist named Andy Ogungbemile that he got in touch wanting to know more.

In his own words; “Andy’s paintings were inspirational and seemed to have a lot of qualities that I lack”. His interest was the genesis of an artistic exchange, whereby Donal would go on to spend 4 months volunteering with The Camberwell Incredibles in order to get to know Andy, observe the way he worked, and ultimately collaborate towards our exhibition of paintings.

If you talk to Donal about the experience, he’s so enthusiastic about how much Andy has taught him and how much he has gained from working together. This partnership has benefited them both hugely: Andy had focused attention, and the chance to work with quality materials that were previously unavailable to him, and Donal has had the insight into a way of working that is so expressive, fun and unselfconscious. What’s been so interesting and hopeful while running Hart Club is how quickly people’s attitudes change when the opportunity to interact with these communities is provided. The visitors to that exhibition are a testament to the fact that when work is given an appropriately elevated platform in terms of presentation and context, attitudes quickly shift.

In the face of this brilliance, what didn’t add up was that in the twenty or so years of their existence as a collective, they had never had a public-facing exhibition in a gallery. It’s no secret that people who have additional needs or have different ways of communicating and behaving are often excluded from mainstream society. As a result, their creative output lies in the shadows.

The broader social implications of this kind of invisibility, or lack of contact, often result in categorisation and negative stereotyping. Our inaugural collaborative exhibition title Training, is a great example of the ways we are trying to challenge these issues. Donal Sturt is a painter and graphic designer I have always really admired – his work is thoughtful, super polished and concise. He came to the Great Mind’s Think Different exhibition, and was so taken by the work of an autistic artist named Andy Ogungbemile that he got in touch wanting to know more.

In his own words; “Andy’s paintings were inspirational and seemed to have a lot of qualities that I lack”. His interest was the genesis of an artistic exchange, whereby Donal would go on to spend 4 months volunteering with The Camberwell Incredibles in order to get to know Andy, observe the way he worked, and ultimately collaborate towards our exhibition of paintings.

If you talk to Donal about the experience, he’s so enthusiastic about how much Andy has taught him and how much he has gained from working together. This partnership has benefited them both hugely: Andy had focused attention, and the chance to work with quality materials that were previously unavailable to him, and Donal has had the insight into a way of working that is so expressive, fun and unselfconscious. What’s been so interesting and hopeful while running Hart Club is how quickly people’s attitudes change when the opportunity to interact with these communities is provided. The visitors to that exhibition are a testament to the fact that when work is given an appropriately elevated platform in terms of presentation and context, attitudes quickly shift.

Love Actually, New York (2018)

In progress shots of collaborative work by Andy Ogungbemile and Donal Stuart 4000mm x 3000mm / Tarpaulin, Oil-based paint, Acrylic, Spray Paint

‘The, ‘ah bless’ way of talking

about the achievements of

neurodivergent individuals

fall away, and there is

genuine appreciation for the

extraordinary outcomes of

these artists’ unique ways

of thinking and creating.’

The problem often lies

with a lack of opportunity

to form organic, firsthand opinions, rather

than inherit preconceived

ones, which are a result

of systematic segregation

and societal pressure

towards conformity.

This is something we are trying to challenge at Hart Club, and why our main curatorial focus is on advocating for collaboration through working relationships. It’s a case of the sum being greater than two parts: bringing people together with very different skill sets in order to enhance what each person contributes to the creative exchange.

Integration, community and creativity are essential to the well-being of everyone. I’m confident that if more people had an insight into what they stood to personally gain from something typically described as ‘giving back to the community’, they'd be queuing to volunteer their time in one way or another. There’s a huge amount of people from all walks of life who feel isolated and undervalued. There are also many things we can all easily do that make a positive contribution to changing this, such as showing people respect and being aware of language.

The reality is that there are increasingly extreme, countrywide government cuts that affect people with disabilities, and indeed the arts in general. With personal funding often only covering the absolute basics, there are fewer opportunities for people with additional needs to engage with stimulating projects. I believe it’s more important than ever to combat these cuts by developing the fourth sector, whereby the work of individuals and organisations adapts to have a specific social agenda at heart.

It is estimated that 65% of people with learning disabilities would like a job, while only 6.6% are in paid employment, most of which is part time. With so few opportunities for conventional paid roles, we are trying to enable neurodivergent artists to receive recognition for their talents. Whilst Hart Club is not commercially driven, by providing a publicfacing platform these artists have an opportunity to be creatively and financially recognised in order to seed funds back into the services that support them. As a Community Interest Company, all profits are reinvested into the project and our finances are transparent.

Throughout this experience, it’s become apparent to me that what we are doing with this model is disrupting power systems. We are trying to encourage a societal shift from preconceived notions of worth and value, to focus less on individual gain, to celebrate that which does not conform to a flawed hierarchical infrastructure.

@hartclublondon

hartclub.org

This is something we are trying to challenge at Hart Club, and why our main curatorial focus is on advocating for collaboration through working relationships. It’s a case of the sum being greater than two parts: bringing people together with very different skill sets in order to enhance what each person contributes to the creative exchange.

Integration, community and creativity are essential to the well-being of everyone. I’m confident that if more people had an insight into what they stood to personally gain from something typically described as ‘giving back to the community’, they'd be queuing to volunteer their time in one way or another. There’s a huge amount of people from all walks of life who feel isolated and undervalued. There are also many things we can all easily do that make a positive contribution to changing this, such as showing people respect and being aware of language.

The reality is that there are increasingly extreme, countrywide government cuts that affect people with disabilities, and indeed the arts in general. With personal funding often only covering the absolute basics, there are fewer opportunities for people with additional needs to engage with stimulating projects. I believe it’s more important than ever to combat these cuts by developing the fourth sector, whereby the work of individuals and organisations adapts to have a specific social agenda at heart.

It is estimated that 65% of people with learning disabilities would like a job, while only 6.6% are in paid employment, most of which is part time. With so few opportunities for conventional paid roles, we are trying to enable neurodivergent artists to receive recognition for their talents. Whilst Hart Club is not commercially driven, by providing a publicfacing platform these artists have an opportunity to be creatively and financially recognised in order to seed funds back into the services that support them. As a Community Interest Company, all profits are reinvested into the project and our finances are transparent.

Throughout this experience, it’s become apparent to me that what we are doing with this model is disrupting power systems. We are trying to encourage a societal shift from preconceived notions of worth and value, to focus less on individual gain, to celebrate that which does not conform to a flawed hierarchical infrastructure.

@hartclublondon

hartclub.org

Artist’s statement by Andy Ogungbemile

Artist’s statement by Andy Ogungbemile

Whiskey Chow in Conversation

With Grace Crannis Article, Issue Three

Article, Issue ThreeMasculinism (2018)

Photo by Orlando Myxx

Whiskey Chow is a London-based artist

and Chinese drag king. With an activist

background in China, Whiskey’s practice

explores female masculinity, stereotypes

and cultural projections of Chinese/Asian

identity with interdisciplinary performance,

moving image and experimental sound

pieces. We met to discuss POWER, the life

of an artist & cultural difference.

/ / / / / / / / / / / / /

Whiskey:

There’s a story about a gay god – the Rabbit

God (兔兒神) in a folktale collection from

the Qing Dynasty. The god used to be

a human and his name was Hu Tianbao.

/ / / / / / / / / / / / /

Whiskey:

There’s a story about a gay god – the Rabbit

God (兔兒神) in a folktale collection from

the Qing Dynasty. The god used to be

a human and his name was Hu Tianbao.

He lived in Fujian province, and loved

a local officer for many years. One

day he couldn’t control himself, and

followed the officer to the toilet to look

at his butt. He got caught. The officer

wasn’t into men, and demanded that

Hu be beaten to death. Hu descended

into the underworld that Chinese

people believe in, and the king in the

underworld asked, why are you here?

You just love that person. You didn’t

hurt anyone. From now on, you will

look after gay relationships.

So Hu

became the Rabbit God.

Nowadays, there’s only one Rabbit God temple in Taiwan and queer people go and worship. Hu was said to be a very pretty man, so he is usually offered sheet masks and makeup as offerings.

Grace:

So there used to be more temples but they got demolished? Is this a story you are exploring with your work?

There was a lesbian musician in Hong Kong called Ellen [Joyce Loo]. In HK there are no other female guitar players like her. She came out a few years ago, but committed suicide last August. I met her 5 years ago when I was promoting independent music in China, I picked her up from the airport and accompanied her to a festival. We were all so shocked by the news of her suicide because she was only 32. But at the time when I met her she was already unwell. So that’s queer despair.

W

Not really. I was born in the late

80s and realised I was queer very early.

To survive you can always queer read

something. Imagine you are the guy in

the movie! I was quite masculine when

I was young, but my mum desperately

wanted a princess.

This kind of conflict never stopped.

In public bathrooms, women would

punish you by talking about your

gender. I sometimes have this

experience in London.

G

I was about to say, obviously you’re

at different points in your life now but

how have you found similarities between

China and the UK?

W

I mean, the people in the UK are much

more chill. But there’s another kind of

hierarchy. I didn’t have to realise that I’m

an Asian woman in China. But living here

is adding a layer. In the queer/lesbian

community here, I’ve been described

as a ‘soft butch’. In China they see me

as a very masculine woman. In the UK

I’m not considered that masculine.

I don’t like the labels, but it’s really funny. My work incorporates these themes in different directions. Mainly it’s about identity, female masculinity, queerness, Chineseness.

W

Yeah I mean I when I look back,

I found I really like to use liquid, like

how do you find a material to describe

queerness? You can’t totally control it. It could go anywhere. I have the shirt,

I live with everything in my living room.

Drowning in paint like a weird museum.

Sometimes I just buy materials because

I think I can do something with them.

Nowadays, there’s only one Rabbit God temple in Taiwan and queer people go and worship. Hu was said to be a very pretty man, so he is usually offered sheet masks and makeup as offerings.

Grace:

So there used to be more temples but they got demolished? Is this a story you are exploring with your work?

W

I’m still researching, but some people say it was made up because they can’t find anything in the Qing Dynasty, but even if the stories were there, they would have been destroyed in the cultural revolution. But the whole work is about queer despair and queer hope. Queer people never have a god to protect them, the best they can see is a queer idol. But unfortunately, queer idols also often end up having tragic stories.There was a lesbian musician in Hong Kong called Ellen [Joyce Loo]. In HK there are no other female guitar players like her. She came out a few years ago, but committed suicide last August. I met her 5 years ago when I was promoting independent music in China, I picked her up from the airport and accompanied her to a festival. We were all so shocked by the news of her suicide because she was only 32. But at the time when I met her she was already unwell. So that’s queer despair.

G

When you were growing up did you have someone like that to look up to, that was openly out?W

Not really. I was born in the late

80s and realised I was queer very early.

To survive you can always queer read

something. Imagine you are the guy in

the movie! I was quite masculine when

I was young, but my mum desperately

wanted a princess.

This kind of conflict never stopped.

In public bathrooms, women would

punish you by talking about your

gender. I sometimes have this

experience in London.

G

I was about to say, obviously you’re

at different points in your life now but

how have you found similarities between

China and the UK?

W

I mean, the people in the UK are much

more chill. But there’s another kind of

hierarchy. I didn’t have to realise that I’m

an Asian woman in China. But living here

is adding a layer. In the queer/lesbian

community here, I’ve been described

as a ‘soft butch’. In China they see me

as a very masculine woman. In the UK

I’m not considered that masculine.

I don’t like the labels, but it’s really funny. My work incorporates these themes in different directions. Mainly it’s about identity, female masculinity, queerness, Chineseness.

G

I came to your performance at Cafe Oto with Victoria Sin. You tend to use a lot of paint, and yoghurt and liquid, sticky things. Do those materials come naturally to you? Is there something about the materiality of it? And the patination of your shirt afterwards. Do you still have it?W

Yeah I mean I when I look back,

I found I really like to use liquid, like

how do you find a material to describe

queerness? You can’t totally control it. It could go anywhere. I have the shirt,

I live with everything in my living room.

Drowning in paint like a weird museum.

Sometimes I just buy materials because

I think I can do something with them.Unhomliness (2018)

Photo by Alice Jacobs

Truth is not always comfortable. It’s so easily read as conflict.

G

I like that too, you never know when you’ll experience something that will trigger a new way to think about an object or a material. Hard for storage but nice for life.W

When you own them they also own

you. When you have to face them every

day, they also talk to you. The living

room is very noisy, because they are

there. I think because of my star sign,

I’m really obsessed with stability.

G

What’s your star sign?W

Capricorn

G

I’m Gemini. You like stability?W: Yeah I guess so. Also I’m a big control freak (lol). But I don’t always know. I feel the audience, which comes from instinct. Somebody once said I was using my life energy to do work. I don’t have a clear story to tell the audience. They don’t need to know it, they need to feel it. You know workout culture, it’s become a new religion. I think this work is coming from that.

G

Yeah, I don’t subscribe. But it’s this whole thing about optimisation of the body, and of life. Fit it all in and get results quickly. There’s so much productivity guilt!W

Yes of course, who can escape?

I’ve seen people pushing so hard to

promote themselves. You can’t say

no! But it’s about your energy and

task management.

G

Really unsexy but so fundamental. It’s also a luxury to say no. And that’s something that I constantly re evaluate my relationship with. I’m getting better at saying no in personal relationships, but if a friend says can you help me with this, or anything that’s work related I feel pretty obligated to say yes.W

In other people’s eyes, the artist

are chill, living the life they want.

People can see your CV wow you’re so

blah blah blah, but they never know

when you are really unwell and have

to force yourself to finish the show.

Now my family see that my career is

progressing and leave space for me,

but I struggled a lot as a teenager. My

parent’s generation cannot understand

or imagine my lifestyle. I completely

abandoned theirs. But if I could have

been happy with it, everything would

have been so easy. I’d get everything they arranged. But I was fighting hard to do what I want, even before I knew what I wanted.

G

How did you win them over? Or do they see that you are doing what you want to do?W

There was so much cultural stress,

but they didn’t force me to get married

and were glad I could study abroad.

They are very happy, I’ve got a job, it

looks decent, I’ve got shows in some

institutions where they can use the

name to show off. I wouldn’t tell them

when my life is difficult, but I tell them

oh I’ve got a screening in the British

Museum, I’ve got a performance in the

V&A. I share the good news only, and

send them the Wikipedia links.

G

Look mum I’m in a museum!W

And I studied performance! You

know nothing about your life/career/

future. But in the UK art world, people

respect each other in work, no matter

how much they pay you. For me it’s an

ideal place. You don’t have to spend

time only talking with people about

housing, kids, money, but not talking

about their dreams. G

Yeah I completely understand. It’s sad that that’s almost the first thing to go sometimes in conversations. How to move onto the next pre-defined step in life.W

It’s always that inspiration from my

new work or from other people’s work

that makes me survive, I’m so longing for

that intellectual engagement, I guess.

G

Do you feel like you have that?W

Yeah I have that. But there comes

another kind of despair when you can

look at or think about the truth more

easily. Some people prefer to play in

safe mode. Honesty, truth and deepness

are really really important for me. It

sometimes makes you very direct and

this kind of quality is sometimes not that

beneficial in your social life…

G

Omg yes. Because people don’t like it sometimes. The whole relationship between directness/honesty and forcefulness. But for me it’s hard to not have the chance to communicate openly. Do you see what I mean?W

Truth is not always comfortable.

But it’s so easily read as conflict, or they

are worried about breaking harmony.

I’m not putting any kind of judgement

about is better, but sometimes there are

stereotypes that direct people are tough

or hard to please.

G

Still working on that one. But also you don’t always have to communicate in the same way. You formulate your own way to relate to each other, even if it’s not the same.W

Yeah I remember when I was young,

I could feel the texture of people. Before

knowing them completely, the texture

is abstract. Over time, their character

still belongs to the texture you feel at

the beginning.

G

You do just know sometimes.W

It’s also your own emotional

engagement? Taking your energy as well

to feel that in a person? I don’t know I

think sometimes I’m just too serious you

know! With a serious face, like a mask,

always frowning.

G: Aha I saw a meme about this, literally what we were just saying. Okay. Ready for a two pronged question. What does power mean to you? And when do you feel most powerful? You can eat your tangerine and think about that cos it’s #deep.

W

Okay I’ll try to answer. Power is when

you are still able to collect or create

the possibility to make changes you

want to see. Mmm. I’m thinking of the

relationship between power and hope,

powerlessness and hopelessness. But

being positive doesn’t always mean you

are powerful. I felt frustrated when I was

25 and I thought I was nobody. My friend

said, why are you trying to compare your

life with that 50-year-old life! They have

used their entire maturity to achieve that!

G

Mmmhmmm

W

Back to what kind of moment makes

me feel powerful. I don’t know, I think

powerful doesn’t mean that I have

a lot of power. It can be peace. Feeling

secure. I think the most desperate

thing is losing a sense of belonging.

Or not knowing where you’re going, or

not caring, or wanting to do anything.

That’s quite vulnerable and powerless.

So powerful for me is willing to say

‘yes I do’ every day.

G

It’s a super hard question. What really interested in is yeah, all of those emotions, or even allowing yourself to feel any emotion is powerful too. Allowing yourself to be sad. And not always beating yourself up for not being perfect, or perfectly happy.W

That’s the thing that life experience

in the UK taught me, and performance

art has taught me. I mean when I just

moved to the UK I could understand

60% of what people were saying. For

the rest I had to pretend, ‘oh yeah,

mmm interesting’. In China, I had

networks, knowledge, resources,

confidence. When I came here, they

were gone. I had to learn all over again,

and accept you will feel panicked, you

will feel nervous. You will say the wrong

words. I’m not used to embracing my

vulnerability. When you perform, you

have to do something, whether you are

prepared or not. You might experience failure. And people are watching. That’s such a lesson. It changed my whole life.

One friend in China posts interviews on WeChat to show young people alternative lifestyles. She asked me – what’s the difference between your art and your life? And I said, okay, if you are not considering your professional career, you can pull out of a show and say I’m not doing it.

You don’t need to do it. But for life, you can’t say I quit. You have to deal with that shit. I think that’s the main difference!

whiskeychow.com

@whiskeyciao

Macho (2017)

Photo by Ray Anyi Ren

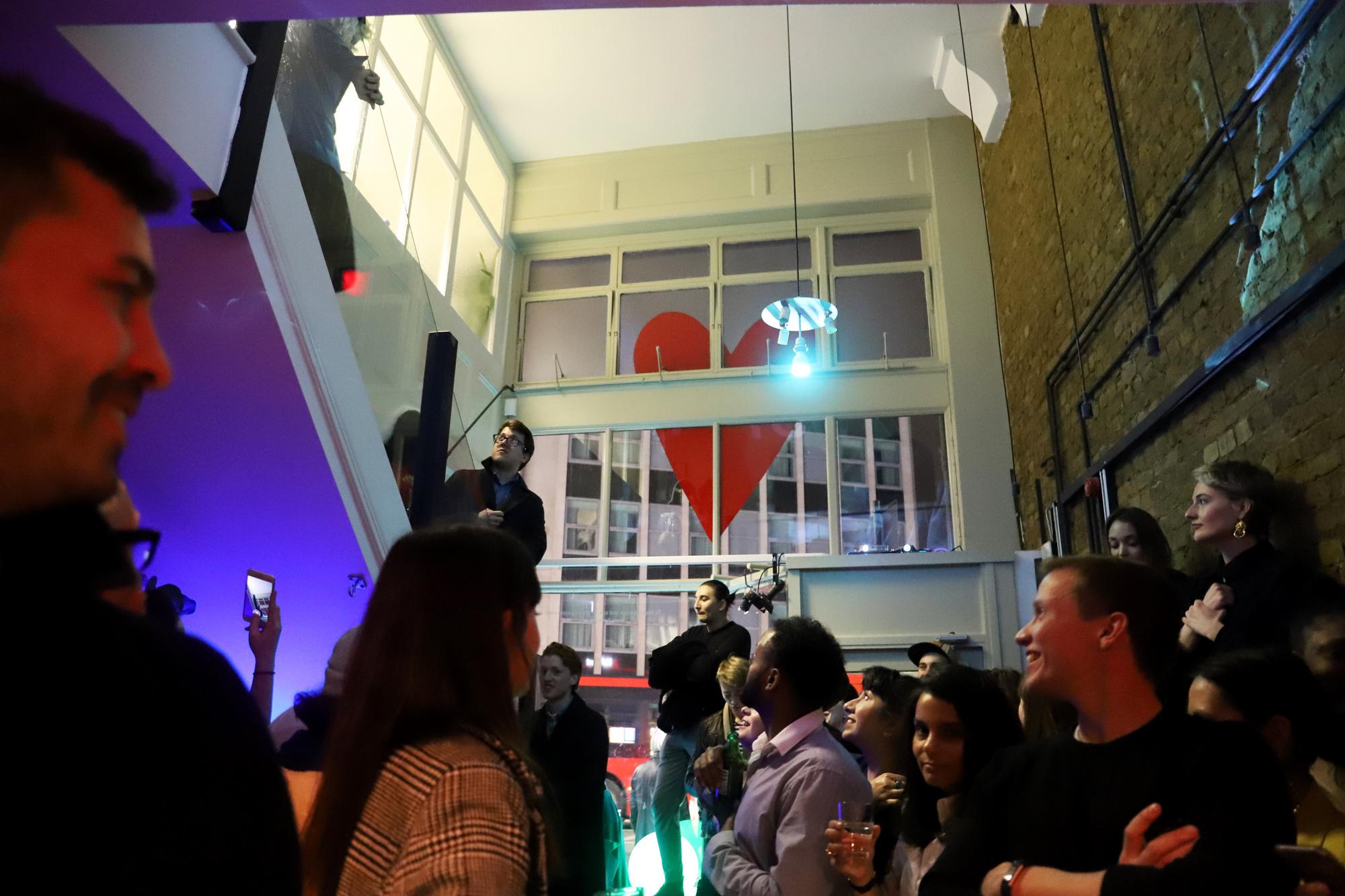

Issue 3 launch party

Event, 2019

Event, 2019The POWER Launch Party

Saturday 9th March @ Hart Club, SE1 7HR

Saturday 9th March @ Hart Club, SE1 7HR

Credits

Performances

Alice Briselden-Waters

Parbati Chaudhury

Dosa & Polly Filla (TAKE ME HOME Projects)

DJ

Dalila

Venue

Hart Club London

Issue Contributors

Adaptive Capacity / Alex Qin / Alice Briselden-Waters / Alice Soulard / Eden Topall-Rabanes / Em Cole / Takeover by Fresh Magazine / Hannah Brewin / Hanna Schrage / Hart Club / Jenny Novitsky / Karel Kingsley / Lucy Hall / Parbati Chaudhury / Protest Press / TAKE ME HOME Projects / Violet Del Toro / Whiskey Chow / Xiao-Wei Lu

︎

A Bottle of Milk

Sara Jafari Article, Issue One

Article, Issue One

"Sara went to buy milk from the shop today," my Grandma later said both proud and weary.

And it was a big deal; I had to beg my uncle to let me go. My mum gave me their address on a piece of paper and put it in my coat pocket. Three times my uncle got up to go himself, insisting that buying milk was no problem.

"But I want to go," I pressed in my broken Farsi. "I'm so bored here, I've been stuck in this house for days!" I said in English to my mum.

"I know, I'm sorry," she said, persuading them that I would be fine, that I could call if I got lost walking the straight, three minute line to the local shop and back.

And it was a big deal; I had to beg my uncle to let me go. My mum gave me their address on a piece of paper and put it in my coat pocket. Three times my uncle got up to go himself, insisting that buying milk was no problem.

"But I want to go," I pressed in my broken Farsi. "I'm so bored here, I've been stuck in this house for days!" I said in English to my mum.

"I know, I'm sorry," she said, persuading them that I would be fine, that I could call if I got lost walking the straight, three minute line to the local shop and back.

Eventually, they let me go. This is what triumph feels like. I pulled my long coat around me tightly, fixed my hijab so that a little bit of hair showed but not too much. I didn't want any attention but my round face did not suit the hijab.

This is not the story of a seven-year-old. This is a story of a twenty three year old girl visiting Tehran where her relatives live.

It isn't that women are forbidden to go outside alone, or that every family wants the girls to stay inside, but they fear that I will get lost and never find my way home, and/or that someone will kidnap me (which happened to my mum once).

The walk to the shop was both liberating and uncomfortable (and hot). Being alone for the first time in days was much needed - something I took for granted living in London. I put my headphones in, stopping every so often for cars to pass me; the street my grandma's house is on doesn't have a pavement.

A young boy stood by his house gave me a weird look as I passed. A look that read 'you do not belong', which is funny because I have also been given this look many times in England. Does my face somehow give away that I do not belong? It is strange because in Iran I felt I visually belonged; people here look like me and I look like them. They have similar eyes, usually crooked noses (nose jobs are common in Iran), and a general look not easy to describe but easy to detect. And, of course, they speak the language I grew up hearing my mum and dad argue in. This said, I felt strongly that I didn’t belong.

Turning left onto the main road there were groups of boys, I could feel them looking at me, seemingly judging me for an unknown crime. I questioned my outfit choice. Underneath my just-above-ankle length coat, I wore a dress with black tights. Could they see my legs in the tights? Was it my fault they stared? Did they think badly of me because of it? I tried to look confident. I look like you so leave me alone.

Both shopkeepers fell silent as I entered.

"Salam," I said weakly. Did they even say hello to shopkeepers here? Maybe not because neither of them said hi back.

I walked straight for the fridge, picked out the milk and handed it to the cashier. He said nothing. I said nothing. I gave him the notes my mum gave me.

"You don't speak Farsi?" He asked.

"A little, not a lot," I said with a nervous smile.

He gave me my change and I left.

How embarrassing. All I had said was hello and he guessed that my Farsi was weak/near nonexistent.

"How pretty," a man said, stopping his car by me, his head out of his window.

I looked around, milk in hand. There was no one here but me. Seriously? With a hijab and my long ass coat, which left a lot to the imagination, I was being cat called? I rolled my eyes, muttered "fuck off" and walked on.

This happens in England. But I had imagined that in my grandma's religious area it would not. What exactly was pretty? My long black coat? Black hijab? He couldn't even see my face when he drove towards me, so it wasn't my face.

Another driver in another car spoke at me. I didn't understand, but from his tone I knew it to be of similar intent to the first man.

I blamed myself. Was the 4cm of ankle under 40 denier too risky? Was I asking for the comments? Why could I not just follow the rules and wear trousers under my coat in 38 degrees like all the other women? Was this happening because I was an outsider and dressed inappropriately, or are these men just perverts like the cat callers in England?

I returned to my grandma's house deflated and defeated. I couldn't tell them what had happened, it was infuriating.

A seven minute journey (it lasted two songs), and these men had treated me like meat. Why? Because I am a woman, I was walking alone.

I did not get kidnapped, nor did I get lost, but my confidence was shattered. I had reverted to a child-like state: five years living alone in London made redundant in seven minutes. I didn't go to the shop alone again because it was clear that I didn't belong, that I couldn't blend in as I’d hoped. I didn't want to deal with the shame I was made to feel for having a vagina. Knowing how much persuading it took to be let out made the triumph bitter.

All this for a bottle of milk.

This is not the story of a seven-year-old. This is a story of a twenty three year old girl visiting Tehran where her relatives live.

It isn't that women are forbidden to go outside alone, or that every family wants the girls to stay inside, but they fear that I will get lost and never find my way home, and/or that someone will kidnap me (which happened to my mum once).

The walk to the shop was both liberating and uncomfortable (and hot). Being alone for the first time in days was much needed - something I took for granted living in London. I put my headphones in, stopping every so often for cars to pass me; the street my grandma's house is on doesn't have a pavement.

A young boy stood by his house gave me a weird look as I passed. A look that read 'you do not belong', which is funny because I have also been given this look many times in England. Does my face somehow give away that I do not belong? It is strange because in Iran I felt I visually belonged; people here look like me and I look like them. They have similar eyes, usually crooked noses (nose jobs are common in Iran), and a general look not easy to describe but easy to detect. And, of course, they speak the language I grew up hearing my mum and dad argue in. This said, I felt strongly that I didn’t belong.

Turning left onto the main road there were groups of boys, I could feel them looking at me, seemingly judging me for an unknown crime. I questioned my outfit choice. Underneath my just-above-ankle length coat, I wore a dress with black tights. Could they see my legs in the tights? Was it my fault they stared? Did they think badly of me because of it? I tried to look confident. I look like you so leave me alone.

Both shopkeepers fell silent as I entered.

"Salam," I said weakly. Did they even say hello to shopkeepers here? Maybe not because neither of them said hi back.

I walked straight for the fridge, picked out the milk and handed it to the cashier. He said nothing. I said nothing. I gave him the notes my mum gave me.

"You don't speak Farsi?" He asked.

"A little, not a lot," I said with a nervous smile.

He gave me my change and I left.

How embarrassing. All I had said was hello and he guessed that my Farsi was weak/near nonexistent.

"How pretty," a man said, stopping his car by me, his head out of his window.

I looked around, milk in hand. There was no one here but me. Seriously? With a hijab and my long ass coat, which left a lot to the imagination, I was being cat called? I rolled my eyes, muttered "fuck off" and walked on.

This happens in England. But I had imagined that in my grandma's religious area it would not. What exactly was pretty? My long black coat? Black hijab? He couldn't even see my face when he drove towards me, so it wasn't my face.

Another driver in another car spoke at me. I didn't understand, but from his tone I knew it to be of similar intent to the first man.

I blamed myself. Was the 4cm of ankle under 40 denier too risky? Was I asking for the comments? Why could I not just follow the rules and wear trousers under my coat in 38 degrees like all the other women? Was this happening because I was an outsider and dressed inappropriately, or are these men just perverts like the cat callers in England?

I returned to my grandma's house deflated and defeated. I couldn't tell them what had happened, it was infuriating.

A seven minute journey (it lasted two songs), and these men had treated me like meat. Why? Because I am a woman, I was walking alone.

I did not get kidnapped, nor did I get lost, but my confidence was shattered. I had reverted to a child-like state: five years living alone in London made redundant in seven minutes. I didn't go to the shop alone again because it was clear that I didn't belong, that I couldn't blend in as I’d hoped. I didn't want to deal with the shame I was made to feel for having a vagina. Knowing how much persuading it took to be let out made the triumph bitter.

All this for a bottle of milk.

Spiral

Celia Graham-Dixon in Conversation withEmily Briselden-Waters

Interview, Online

Interview, OnlineAs part of Hysteria, a series of events organised by Ladybeard magazine, feminist art and design magazine Syrup is hosting Spiral, a creative exploration of anxiety through the modes of moving image, installation and film screenings. To discuss her work and the idea behind the event, Emily Briselden-Waters, participating artist and Syrup co-editor talks to writer and researcher, Celia Graham-Dixon.

C

As a starting point, I’d like to talk about the idea behind putting on an event like Spiral and in what ways it comes out of the work you do at Syrup Magazine. It seems that it’s been important for you to give space to different interpretations of anxiety and how thinking of it through a feminist lens gives way to distinct visual languages that it can be explored or illuminated by. All the work in the show is in some way screen-based, which draws out the immersive abilities and affective qualities of this surface. Immersion is a state that pertains both to artistic involvement and anxiety, in what way is this a key theme running through both the event and Syrup as a wider project?E

I don’t think we can talk about mental health without talking about gender, so the show tries to give a voice and a platform to anxiety as a feminist issue. Immersion was an important factor in thinking of how to present the work and how to physically envisage the theme. Screens are used in several different ways throughout the space. Some of the works use screens in an installation context, while others present collage and drawing digitally. There is also narrative film, which calls for a more focused viewing experience and a different type of immersion. We wanted to think about different ways that work can be shown and new ways that the theme can be explored. It needs to be an open and varied discussion because everyone has their own experience that leads them to the point of anxiety. This speaks to the ethos of Syrup too, which I created with Grace Crannis as a way of exploring how creativity and design can be used as tools for change. We wanted to rethink what a feminist publication could look like and create a well-designed piece of activism that people want to sit down with and read.C

I’m really interested by this attempt to visualise and give form to anxiety, both through the individual works and how they interact with each other in the space. In some ways, this gives materiality to something that is intangible and nebulous, but in other ways it draws out the material qualities of this state, which can often engage and test the body in unexpected and challenging ways. Can you tell me a bit about how you explored this in your MA project, Circus of Anxiety?E

The physicality of anxiety was a key element for me and something that kept coming up throughout the project. I did a lot of interviews with medical professionals and people who suffer from anxiety and every time I asked people why there was a stigma around anxiety, they’d say it’s because you can’t see it. I wanted to explore how tangible anxiety can be and how internal thought gives way to physical experience, which is why I used installation, projection, costume and set design to try and communicate this. This is also something that comes up in Shelter, Sheltered, the piece by Grace, Emilie and Jenny. Their work looks at physicality from the opposite direction and envisages the ways that domestic physical space can lead to and have an effect on the way we experience anxiety. This is echoed again in the show’s narrative films, which deal with the affective power of familial and cultural spaces.C

The use of different physical and immersive elements in your work emphasises the need to affirm the realness of anxious experience. As well as touching on the stigma attached to mental illness and the myth that they are somehow less ‘real’ than other illnesses, this also suggests the need to create a new visual language or set of explicative or interpretive gestures to explore anxiety. In what sense do you think the realm of art and specifically feminist art can offer new and productive ways to discuss these issues and form strings of connection for people?E

The initial idea for my work was based around hysteria and how it’s been historically performed. I was trying to reclaim this element of performance and gesture and rephrase it in a celebratory way. I wanted to use my work to explore how women can reclaim their physicality and their bodies in relation to this illness. In a sense, I’ve mirrored the processes of how anxiety has been performed historically, but I’ve tried to do it through a feminist lens and claim more ownership of the body. A lot of the references in my costumes are from Bauhaus. This aesthetic mirrors the geometric and circular shapes that were produced when I asked people to draw their anxiety in the beginning stages of the project. This also echoes the idea of rumination, overthinking and spiralling, hence why we chose of ‘Spiral’ as the name of the event.C

With hysteria being historically, and indeed etymologically, associated with women, it seems crucial for women to reclaim the conversation about our mental health as a political issue and to consider the part social factors play in how each of us experiences or is treated for anxiety. The way anxiety and mental health is understood, both within the health service and outside, can often overlook issues of race and class. This is where the politics of self-care comes in, which black feminism has already done so much to show is a radical act for women of colour. Audre Lorde said that self-care is an act of self-preservation and political warfare and more recently Angela Davis has spoken about it as an important aspect of holistic political organising.E

If we’re going to talk about anxiety as a feminist issue, we need to do that in an intersectional way. It also comes down to language and what language we’ve been given or been given the right to use in relation to our mental health. This makes me think of the work that Arts Sisterhood UK have done, which was set up by Ali Strick as a direct response to the growing cuts to mental health services. They run affordable art therapy classes for women and non-binary people, which speaks to the importance of giving people new ways to visualise and communicate emotions and mental health. When I asked people to draw their anxiety for my project, I was interested in people’s ability to give their anxiety imaginative form. The process of creativity is one of self-care, so it was important for me to include this aspect in the project. This is a notion that is also present in Rachel Davey’s hand drawn illustrative work.C

I’m interested in the question of whether art has transformative capabilities, for both the maker and the viewer. In terms of the screen specifically, its textured and tensile qualities give it a material agency that has the ability to draw viewers in and provide the possibility of an affective aesthetic encounter. I have seen the screen be harnessed as a surface of connectivity and compassion, both of which seem crucial in a discussion about anxiety. This is something that Hanna picks up on in The Thin Layer, which incorporates VR – the so-called medium of compassion. What role do you think artistic practice and specifically screen-based media play in helping move people out of certain states?E

This brings us back to the idea of immersion and the crucial part it plays in art’s affective power. This is something Lily explores in Walking the Long Way Home, which is filmed from the perspective of a woman walking home at night. This puts you in an immersive space, which speaks to anxiety as a very personal and subjective experience. Hanna’s use of VR picks up on the way that we understand and process through experience. She shows how the medium can be used as a visceral communication tool to help people understand anxiety, which is also a visceral experience. What’s also interesting is the paradox between technology helping us to understand anxiety on the one hand, but also reinforcing it on the other. This is particularly contentious in terms of social media.C

This exhibition has given you the opportunity to open up the theme of anxiety to several different artists and I’m interested in what effect that has had on your understanding of the theme and of your own work.E

Anxiety and making work about anxiety are both such personal experiences, but it’s been really important to collaboratively explore the different layers of how people think about it. Everyone has their own individual relationship and response to the theme. The process of putting the event together has led to a very strong and diverse body of work. The show is so much better for having several different interpretations – we want Spiral to be a celebration.Celia Graham-Dixon is a writer, researcher and editor based in Amsterdam.

Visual identity by Hanna Schrage

Visual identity by Hanna Schrage